Gasgoo Munich - The US stands as the world’s second-largest auto market—a massive, high-profit arena. Total sales surpassed 16.2 million units in 2025, including roughly 1.21 million pure electric vehicles, 280,000 plug-in hybrids, and about 2 million hybrids. Yet Chinese-built cars are virtually absent from the showroom floor. The US imported only about 116,000 passenger vehicles from China in 2024, accounting for less than 1% of total new car sales and rendering them nearly invisible at retail. A combination of steep tariffs, technology and data red lines, and a lack of brand recognition has erected a formidable glass wall.

That, however, does not mean Chinese automakers lack presence in the US.

In fact, CATL has entered Ford’s supply chain through technology licensing, while components suppliers like Huayu and Joyson have set up plants in Mexico, using USMCA rules of origin as a springboard to supply the Detroit Three. Waymo’s autonomous driving system runs on Nvidia chips, and Nvidia’s autonomous ecosystem has long involved collaboration with Chinese companies and engineering teams. Certain aftermarket parts channels are also dominated by Chinese firms. According to US Department of Commerce data, China ranked as the third-largest source of US auto parts imports in 2024, with an import value of approximately $18.26 billion, representing a 9.3% share.

Put simply, the Chinese auto industry is absent from US showrooms, not from the market ecosystem itself. At deeper levels of the supply chain and technical cooperation, China’s industrial chain has already achieved an “embedded presence.”

In this episode of “Xiaoying Says,” we focus on the US market—a strategic landscape that appears to be closing its doors yet remains critically important.

I. A High-Profit Market Siege: Large and Stable

On the global automotive map, the US remains a market that cannot be bypassed—yet it is incredibly complex.

By scale, the US is the world’s second-largest single auto market after China, with annual new car sales consistently stable in the 15–16 million range and a used car market that continues to expand. Structurally, it is one of the most profitable markets globally per vehicle, with the average selling price for new cars in 2025 approaching $50,000. The high proportion of pickups, large SUVs, and premium models makes the US market highly attractive to OEMs and core component suppliers alike.

For this reason, even as tariffs, political risks, and policy uncertainty continue to rise, the US remains a market global automakers and supply chain companies are psychologically unwilling to abandon.

American consumers tend to be rational, prioritizing long-term reliability and maintenance costs while showing a clear preference for established brands and heritage. They are not averse to new technology, but their adoption path is relatively cautious. This explains why traditional brands still command a strong defensive moat in the US, while new brands often require a longer cycle to build trust.

II. Stable Competitive Landscape, Unfriendly to New Brands

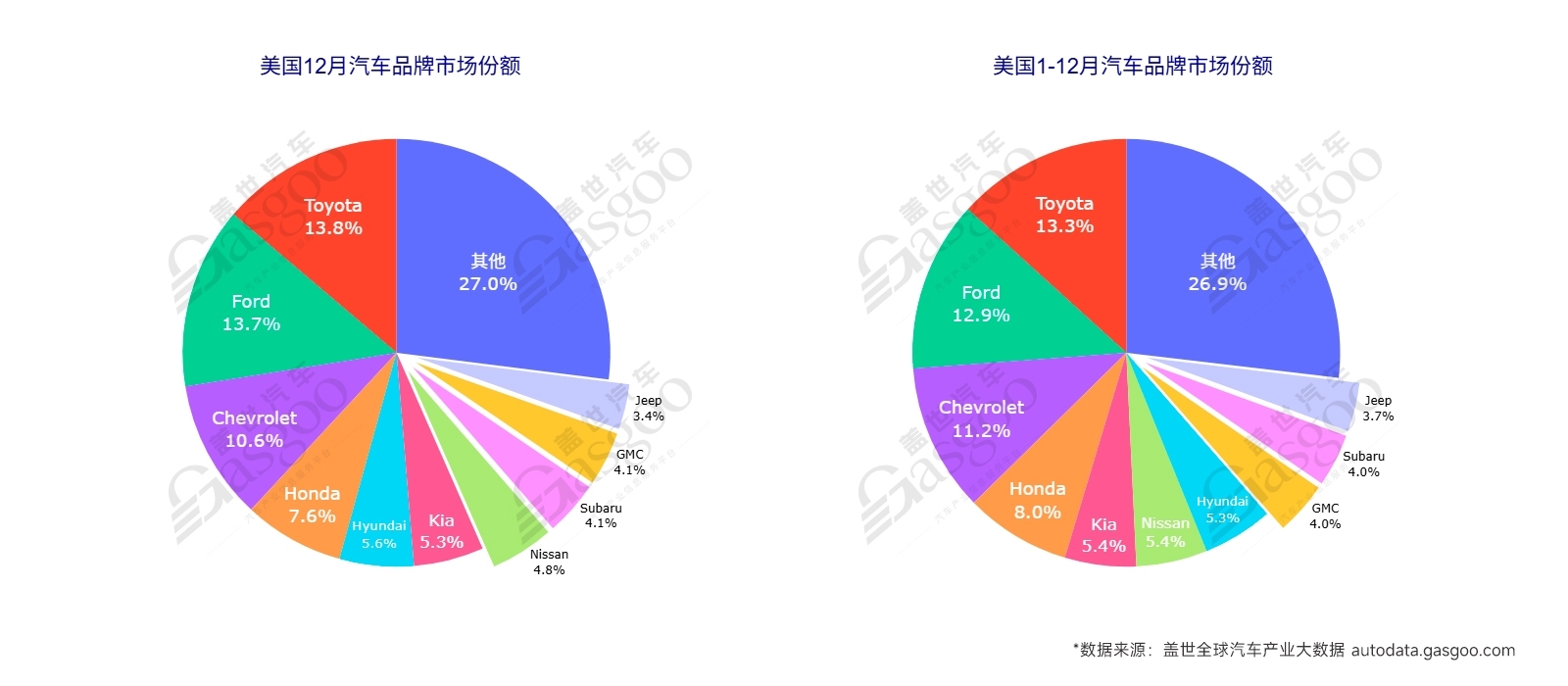

According to the latest statistics from Gasgoo Auto Research Institute, the Toyota, Ford, and GM groups combined accounted for over 40% of new car sales in the US market in 2025. Meanwhile, Hyundai-Kia and Stellantis contributed nearly another 20%. The market is highly concentrated among a few top players. This concentration makes the US market extremely hostile to new entrants, further raising the barriers for brand building, distribution channels, and localized operations. Specifically:

1. The Detroit Three: Still Holding the “Fundamental” Market

General Motors has long maintained the top spot in sales among US groups, with a market share of about 16–17%; Ford holds roughly 12–13%.

Stellantis (Chrysler, Jeep, Ram, etc.) holds about 9–10%. Together, the three occupy roughly 38–40% of the US new car market, forming the market’s most solid foundation. Their advantage is particularly pronounced in high-margin segments like pickups, large SUVs, and commercial vehicles.

2. Japanese and Korean Brands: The Most Successful “Outsiders”

In the US market, Toyota is the largest-selling single foreign brand, with a market share of about 14–15%; Honda holds roughly 8–9%; and the Hyundai-Kia group accounts for about 10–11%. This means Japanese and Korean brands combined hold nearly 30% of the US market, with exceptional stability. Through long-term localized production, mature dealer networks, and a reputation for reliability, they have established a firm “second camp” in the US and remain the most successful non-American force in the market.

3. New Energy Players: High Influence, but Small Volume

Looking at the overall sales structure, the penetration rate of new energy vehicles in the US market is currently only about 10%—significantly lower than in China and Europe. New energy remains an “incremental segment” rather than a mainstream one, and the electrification process continues to slow.

Within the new energy sector, Tesla remains the absolute leader in the US electric vehicle market, with a share of about 40% in the pure electric segment. However, within the broader US passenger car market, Tesla’s total share is still only 4–5%. Other new energy players like Rivian and Lucid have some influence in niche segments, but their overall sales volume remains limited and is insufficient to alter the competitive structure of the US market.

Image Credit: Tesla

In summary, the US automotive market is a highly stable structure firmly controlled by traditional giants, deeply cultivated by Japanese and Korean brands, and seeing local breakthroughs in new energy. In this competitive environment, for Chinese vehicle brands to gain visibility in the US market, the challenges go far beyond product competition. They face a compounded mix of structural, channel, regulatory, and long-term operational hurdles—alongside high tariffs, an uncertain policy environment, and unfriendly brand perception.

III. Vehicles Exit, Capabilities Remain

The US is one of the world’s largest auto importers, yet the share of imported vehicles from China has long lingered at a minimal 1–2%. Chinese vehicle brands have almost no visibility at US retail outlets. This is not the result of a single policy or short-term friction, but a long-term state formed by the overlapping logic of tariffs, regulation, brand perception, and industrial security. Given this reality, the way Chinese companies exist in the US market is undergoing a fundamental shift—from “selling vehicles” to “providing capabilities,” and from “fighting for terminal visibility” to “embedding into the industrial system.”

From an industrial foundation perspective, the US is one of the most mature regions in the global automotive industry. Its vehicle, parts, software, and engineering service systems are complete, with local supply chains deeply coupled with global ones, and sophisticated R&D, testing, and certification systems. Precisely because of this, US automakers have extremely high requirements for their supply chains: stability, compliance, traceability, and strong local response capabilities.

However, with the continuous offshoring of US manufacturing over the past three decades, nearly 60% of parts used in US auto plants are imported. China and Mexico alone account for more than half of all US auto parts imports. In 2024, the value of auto parts imported from China was about $18 billion, accounting for nearly 10% of total US auto parts imports—significantly higher than the share of complete vehicles.

But we must face a reality: The “de-Chinaization” of the US automotive supply chain has moved from the “discussion” phase to the “execution” phase. The logic behind this is not merely a trade issue, but one of industrial security, technology security, and political and election cycles. Whether through tariffs, subsidy rules, or scrutiny of key components, the US is continuously reducing its direct dependence on Chinese supply chains. Yet, looking at the actual trade structure, the scale of US auto parts imports from China far exceeds that of vehicles. This means the US market cannot—and is unwilling to—completely abandon Chinese capabilities in parts and systems in the short term.

The reason is not complicated: in batteries, electric drives, electronic controls, electronics, and some intelligent hardware, the Chinese supply chain still holds advantages in cost, scale, and engineering maturity. The local North American and allied systems do not yet possess the capacity for full substitution in all segments. Completely severing the supply chain would directly drive up vehicle costs and weaken the competitiveness of US automakers.

Therefore, the true US attitude toward the Chinese auto industry is to reject the direct entry of vehicle brands due to high visibility and sensitivity; yet, it retains low-visibility inputs at the module and system levels, actively reshaping control through localization and compliance. Recently, General Motors, Tesla, and others have demanded that their supply chains shed “Made-in-China” status by 2027, while simultaneously welcoming Chinese suppliers to build plants in the US or Mexico.

Image Credit: Zhongding Group

This also explains an unfolding trend: Chinese supply chain companies remain “within the US system,” but their mode of existence is being forced to change: from direct export to gradual local production or deep processing; from “Made in China” to “a link within the North American system.”

Under this logic, “building local plants in the US” will become a prerequisite for Chinese parts companies to remain retained within the framework of “de-Chinaization.” Only this way can they have a chance to enter the mainstream supply chain of US automakers, pass compliance reviews, and “stay” in the next round of supply chain restructuring. Specifically:

1. Segments That Must Be Localized

Typically, this includes final assembly and system integration (such as assembly of complete units and integration of key modules), production of components directly related to vehicle safety and compliance (involving certification, traceability, and liability definition), and product categories where delivery cycles and supply security are highly sensitive.

Their common characteristic is that any issue directly impacts vehicle delivery; legal liability is clear and cannot be outsourced; and US automakers are unwilling to bear cross-border uncertainty. If a supply interruption occurs at any of these links, it directly affects vehicle roll-off the assembly line, so they must be within the US or the North American region.

2. Segments Where Localization Is Strongly Recommended

This layer is not “legally mandatory,” but it has become a default requirement in commercial practice and a basic threshold for participating in market competition. Typical examples include battery-related packs, modules, and post-stage processes; post-processing and testing of system-level components like electric drives and controls; and modules in intelligent hardware deeply coupled with vehicle systems.

If these segments rely entirely on exports, they often encounter three types of problems: unstable tariffs and costs; prolonged compliance review times; and being viewed as a “supply risk” by the client. Therefore, even if technology and price are competitive, they may be “silently docked points” during the client review phase.

3. Segments That Need Not Be Localized

Typically, this includes large-scale manufacturing of basic components, parts with high standardization and low sensitivity to delivery timeliness, and early-stage manufacturing capabilities where cost efficiency is the core advantage.

These capabilities have low visibility to the end user and low sensitivity to data and compliance; China still holds significant scale and cost advantages. Moving this entire layer to the US is both unnecessary and would weaken overall corporate competitiveness—keeping it in China is actually more optimal.

In summary, the real requirement of the US market for Chinese parts companies is not to move the entire industrial chain over, but to place the “riskiest, most responsible, and most delivery-critical segment” where it can exercise control.

III. Policies and Regulations Reshape the Logic of Entry

China-US trade conflicts and complex geopolitical considerations have made the development of Chinese companies in the US market incredibly challenging in recent years, with the automotive industry bearing the brunt.

1. High Trade Barriers and Tariff Restrictions

The most direct challenge for Chinese automakers entering the North American market is trade barriers and tariff restrictions. North American trade policy is complex and volatile, especially the protectionist policies pursued by the US, which have placed numerous obstacles in the way of Chinese automotive products entering the North American market.

Image Credit: The White House

First is the tariff issue.

As of January 30, 2026, the US implements a multi-layered, clause-by-clause tariff system on Chinese cars and related products. At the vehicle level, electric passenger vehicles (EVs) exported from China to the US bear the following core tariff burdens:

Base Most Favored Nation (MFN) rate: 2.5% for passenger vehicles; Section 301 special tariff: a 100% surcharge on Chinese electric vehicles (effective from 2024, a special rate rather than an independent tax category). In certain execution and calculation scenarios, electric passenger vehicles may also be subject to a 25% national security tariff under Section 232. With these clauses stacked, the comprehensive tax burden can reach approximately 127.5%.

Overall, against the backdrop of the long-term implementation of the 100% Section 301 tariff and the persistent risk of Section 232, the US has formed a substantial, institutional high-tariff barrier against Chinese vehicles, especially electric ones. As of early 2026, relevant additional tariff policies continue to be implemented, with no clear signal of tax reductions or comprehensive exemptions.

Facing the auto industry, the US has not only imposed high tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles but also issued a series of “national security”-related import bans, restricting Chinese cars and related supply chains from entering the US from multiple dimensions.

In early 2025, the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) officially released the “Connected Vehicles Final Rule,” explicitly prohibiting the import or sale of connected vehicle systems designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by Chinese or Russian-related entities starting with the 2027 model year, extending to the hardware level from the 2030 model year onward.

This ban covers vehicle connectivity systems (V2X, cellular, Bluetooth, satellite communications, etc.) and automated driving systems (ADS). For Chinese automakers and smart driving supply chain companies that rely on “intelligence” as a core competency, this is almost a fatal blow. Even if they bypass tariffs through joint ventures or localized supply chains, their smart driving and connectivity functions may still face a “single-vote veto” due to institutional restrictions.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) long ago set another “invisible blockade line” at the supply chain level. Through a federal electric vehicle tax credit of up to $7,500, the act requires that vehicles qualifying for subsidies must be manufactured in North America, and battery materials and components must originate from the US or countries with free trade agreements.

According to the “Foreign Entity of Concern” (FEOC) guidelines issued by the US Treasury and Department of Energy at the end of 2023, starting in 2024, any batteries or key components involving Chinese participation in production or holding are excluded from subsidy eligibility. In other words, even if Chinese automakers build plants in the US, as long as the battery system remains tied to the domestic supply chain, they cannot enjoy policy incentives.

On the surface, green subsidies are essentially the institutional execution of “supply chain decoupling.” The underlying logic is strategic security: using incentive structures to completely strip the new energy industry chain from the Chinese system and reshape a “friend-shored” local manufacturing network. This means the US is restructuring the supply chain system under the guise of “climate policy,” essentially promoting the “de-Chinaization” of the new energy industry.

With the Trump administration taking office, the tilt toward trade protectionism has become even more pronounced. It has not only maintained high tariffs on Chinese automotive products but also plans to terminate federal electric vehicle tax credit policies, reduce incentives for local EV production, and significantly weaken electric vehicle regulatory credit systems. This policy retreat regarding new energy vehicle development deals a multiple blow to Chinese new energy companies entering the US market.

In the realm of investment and supply chains, Chinese automakers also face strict scrutiny.

For example, in May 2025, the US House Committee on Homeland Security launched an investigation into the US electric bus business of a leading new energy automaker, demanding the submission of internal documents regarding company structure and data security practices, citing concerns about potential foreign influence and data leakage risks. Such scrutiny often goes beyond routine commercial scope and carries distinct geopolitical overtones.

2. Sensitive and Negative Public Opinion Environment

Risks at the level of US public opinion are equally significant and cannot be ignored.

In recent years, some US politicians and think tanks have continuously hyped theories of “national security” and “data security threats,” conflating autonomous vehicles, connected cars, and electric vehicles to guide the public toward a negative perception of Chinese technology. Although in reality, due to high tariffs and other reasons, Chinese passenger vehicles can hardly enter the US market, such rhetoric continues to influence the public opinion environment.

As Chinese auto exports continue to surge—ranking first globally for three consecutive years—this achievement is often maliciously distorted as “low-price dumping” or reliance on unfair subsidies, triggering resistance from local industry. Occasional product quality issues may also be amplified and interpreted, serving as fodder for exploitation in a sensitive public opinion climate.

The political and opinion risks faced by Chinese auto exports to North America possess long-term and structural characteristics. These include institutional barriers like high tariffs, import bans, and investment reviews, as well as narrative challenges such as data security stigmatization, accusations of unfair competition, and quality doubts. These risks are deeply rooted in great power strategic competition and the adjustment of global industrial patterns, requiring joint attention and careful handling from enterprises and policymakers.

3. Invisible Institutional Red Lines and Union Politics

The United Auto Workers (UAW) long controlled the negotiation rights of the Detroit Three and is one of the world’s most powerful unions. It cares not only about wages but is deeply involved in key decisions like production arrangements, shift systems, and plant closures. For Chinese companies accustomed to high-intensity, fast-paced production methods, this is tantamount to stepping on the “brakes.”

At the same time, the US political cycle directly impacts industrial policy. When Democrats are in power, the emphasis is on new energy subsidies and climate agendas; when Republicans govern, the focus shifts to fossil fuels and traditional manufacturing. Corporate investment cycles often span more than a decade, but the US policy cycle can flip every four years. This policy uncertainty poses a severe challenge to any corporate decision-making.

The US policy and institutional environment constitutes layers of constraints for Chinese automakers and supply chain companies: subsidies tied to localization, interstate policy divergence, unions, and political uncertainty. Combined, these make entering the US market not merely a commercial choice, but a comprehensive test involving politics, culture, industrial chains, and even geopolitical strategy.

IV. A Strategic Market and Tech High Ground That Cannot Be Abandoned

So the question arises.

Since the US has placed so many restrictions on Chinese companies—high tariffs, tightening entry, and sensitivity—why does the Chinese auto industry still place such importance on the US market?

Because the US is not merely a high ground for sales volume, but also a high ground for technology, rules, and profits in the global automotive industry.

It defines what constitutes a “high-value model,” a “sustainable business model,” and what level of safety, software, data, and intelligent capabilities qualify for entry into the global mainstream system. As long as a company wants to become a truly global automaker or supplier, it cannot bypass the industrial coordinate system represented by the US.

Moreover, the essence of US restrictions is not to “exclude” the Chinese auto industry entirely, but to redraw the threshold for participation. Limiting vehicle visibility and controlling the pace of brand entry is the result of politics and industrial security; yet at the industrial reality level, the US has not—and cannot—completely sever its dependence on Chinese manufacturing capabilities, Chinese engineering capabilities, and Chinese cost efficiency. The only difference is that these capabilities must exist with lower visibility, higher compliance, and deeper embeddedness.

From a longer cycle perspective, the reason the US market is worth the Chinese auto industry’s continuous study and alignment is not about how many cars can be sold in the short term, but that it is a “touchstone market.” The US market dissects a company’s globalization capabilities thoroughly: whether compliance is robust, whether the organization is mature, whether long-term investment is sufficient, and whether there is a genuine understanding and respect for the rules. These issues might be temporarily masked in looser markets, but in the US, there is almost nowhere to hide.

Therefore, for the Chinese auto industry, whether to enter the US is not the only proposition; whether to build oneself according to the difficulty of the US is the true divide. Even if short-term entry into the US retail market as a vehicle brand is impossible, understanding the US, studying the US, and maintaining dialogue with the US system at the supply chain, technology, and rule levels remains an unavoidable lesson on the path to globalization.

From this perspective, the significance of the US market has shifted. It is no longer a “sales target that must be conquered,” but rather a mirror—reflecting whether an enterprise possesses the underlying capabilities to become a global company. Truly mature globalization never starts from the easiest places, but forces evolution amidst the most stringent rules.