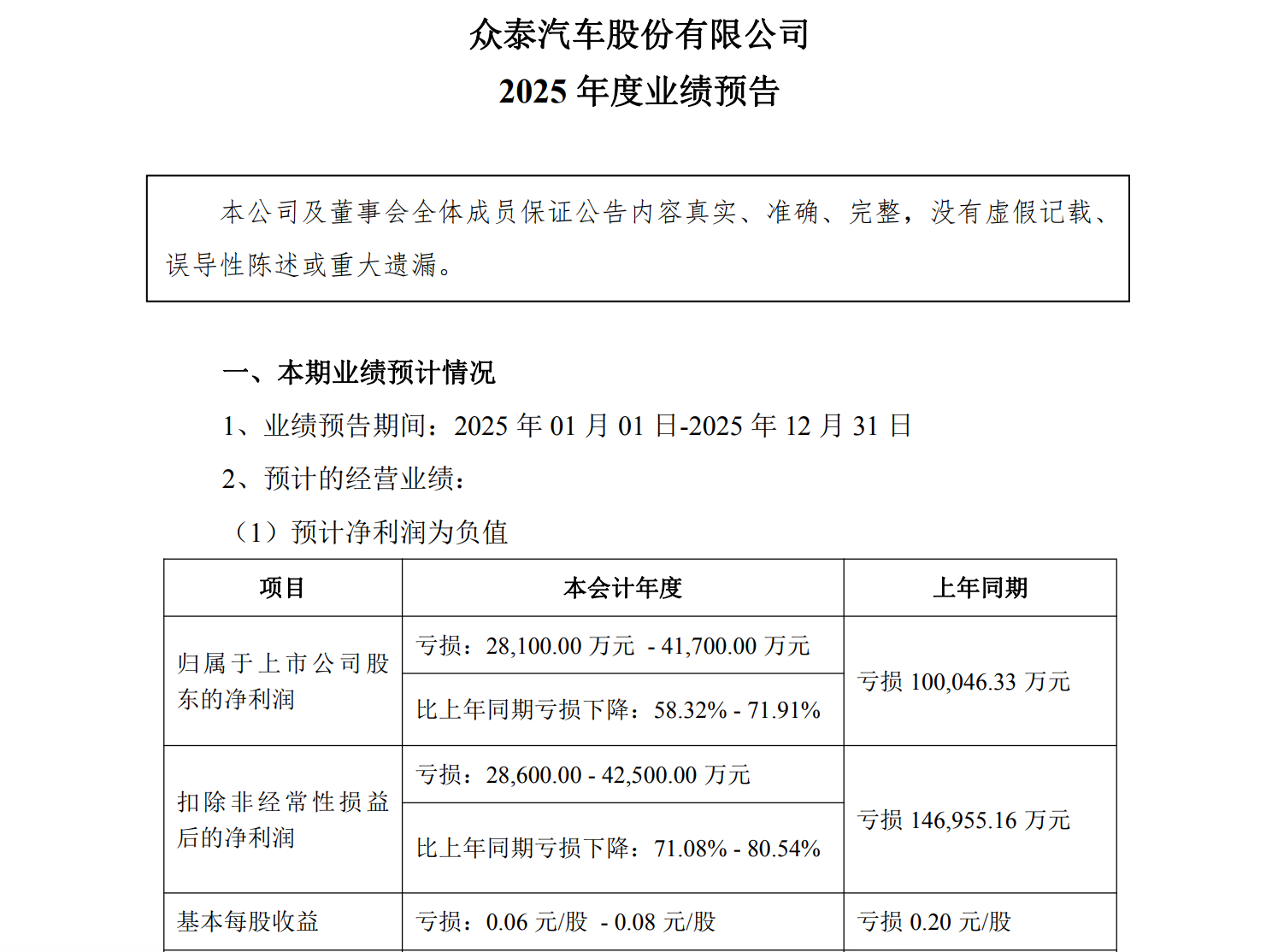

Gasgoo Munich- As 2026 begins, the auto chip shortage appears to be staging a comeback.

During a livestream in early January, Xiaomi Chairman Lei Jun didn't mince words: the new Xiaomi SU7 is grappling with memory costs that are jumping quarter by quarter, adding thousands of yuan to the bill for each vehicle.

Almost simultaneously, Nio founder William Li warned that rising memory prices have become the industry's heaviest cost burden this year, even advising consumers to "buy sooner rather than later." A supply chain executive at Li Auto issued an even starker alert: the supply fulfillment rate for automotive memory chips could fall below 50% in 2026.

Authorities like Wells Fargo, UBS, and S&P Global have issued a cascade of warnings, noting that global automakers could face severe production disruptions and surging costs as early as 2026. That anxiety is already tangible on the factory floor: GAC Honda was forced to adjust its production cadence in January 2026 to cope with the ripple effects of tight semiconductor supplies.

In truth, the auto industry knows the drill when it comes to chip shortages. Over the past few years, the specific categories in short supply have shifted—from MCUs and power semiconductors to today's memory chips. All signs suggest that shortages have never really left the sector.

Chip Shortages: A Persistent Headache

This year's chip shortage feels different from the one in 2021.

The 2021 crunch was triggered by the pandemic, supply chain breaks, and a mismatch in demand. The current pressure, however, is laser-focused on memory chips, driven by the explosive expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) infrastructure.

Automotive memory chips handle the heavy lifting—storing and rapidly reading vehicle control software, sensor data, in-car entertainment, autonomous driving algorithms, and system logs. As smart cockpits, driver-assist systems, and centralized electronic architectures become standard, the demand for storage capacity per vehicle keeps climbing. A mainstream L2-level new energy vehicle now requires about 150G of storage just for the cockpit—several times what was needed just two or three years ago.

In other words, for intelligent vehicles, memory chips are no longer mere "auxiliary components"—they are the infrastructure supporting the entire electronic architecture.

In this cycle of price hikes and shortages, DRAM products like DDR4 and DDR5 are feeling the pinch most acutely.

Global memory giants—Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron Technology—are funneling their limited wafer capacity and capital spending toward the more profitable and voracious AI sector, particularly high-bandwidth memory (HBM) and server-grade DDR5 chips. The explosive demand for high-performance memory in AI data centers is squeezing the already limited purchasing power of the auto industry.

Last November, Reuters reported thatamid a global boom in AI data center construction that has left some memory chips in short supply, Samsung Electronics had raised prices for these chips by as much as 60% compared to September.

Image Credit: Samsung

The auto industry finds itself at a clear disadvantage in this resource allocation game. Estimates from several research firms show that automotive DRAM accounts for less than 10% of the global market, making it difficult to compete with cloud computing and AI clients in terms of purchasing volume or profit contribution. Compounding the issue, the long certification cycles and stringent reliability requirements for automotive-grade chips mean automakers cannot quickly switch models or adopt alternative solutions.

Unlike the past when chips simply couldn't be bought, automakers now face a dilemma where they can secure supply—only at runaway costs—or find that there's simply no capacity left if they want more.As for domestic substitution, it's not impossible in the short term, but the hurdles remain high. While domestic memory manufacturers have made notable strides in technology and production capacity, they still need time to build up track records in automotive-grade certification, consistent supply capability, and cost efficiency at scale.

Beyond memory chips, costs for other semiconductors are becoming unpredictable due to rising raw material prices.

In recent days, numerous chip companies have issued price increase notices. Zhongwei Semiconductor stated that, given the severe supply-demand situation and immense cost pressure, it has decided to adjust prices for MCUs and NOR Flash products immediately, with hikes ranging from 15% to 50%. The company emphasized that if costs fluctuate significantly again, prices will be adjusted accordingly.

Goke Microelectronics also notified clients of price hikes: starting in January, prices for packaged 512Mb KGD (Known Good Die) products will rise by 40%, 1Gb KGD products by 60%, and 2Gb KGD products by 80%. Pricing for external DDR products will be announced separately.

This structural contradiction is already playing out in the real world. Previously, Honda China adjusted its production pace due to semiconductor supply issues; while the company stressed the impact was manageable, the damage was done. Late last year, Nio, facing a chip shortage, adopted a new technical solution for the rear entertainment extension function in its all-new ES8, resulting in the removal of two features.

How to Fix the Shortage?

In the short term, there is no quick fix for the automotive memory chip shortage. Multiple international agencies forecast that global DRAM demand growth will outpace supply growth over the next two to three years, with the supply gap potentially widening further in 2026. Meanwhile, new production lines from major memory manufacturers are not expected to come online until 2027 or even 2028, meaning no substantial capacity increase is imminent.

Against this backdrop, the auto industry's strategy must be "multi-pronged." In the short run, leading automakers are trying to cushion the blow of supply volatility by locking in capacity early, signing long-term purchase agreements, and adjusting vehicle configurations. Yet these measures are largely buffers, not fundamental cures.

Looking at the long term, chip localization is an unavoidable path. On one hand, domestic memory chip manufacturers are accelerating their expansion pace, with some having already entered the automotive-grade market.

Image Credit: Infineon

On the other hand, automakers are also taking a more active role in the chip supply chain, securing leverage through joint development and equity investments. For instance, Li Auto and Nio have begun experimenting with long-term capacity guarantee agreements and even direct joint investment in local memory manufacturers to lock in supply. This shift from "pure buyer" to "deep participant" is becoming an industry trend.

Top-tier players like Tesla and BYD are attempting to achieve autonomy over core control units by self-developing AI chips or building their own semiconductor production lines.

Furthermore, restructuring electronic and electrical (E/E) architectures is equally critical. By improving chip universality and reducing reliance on specific models, automakers hope to mitigate future supply risks to some degree.

Moreover, compared to the risk of total production shutdowns a few years ago, the current pressure is felt more in costs and localized supply tightness—creating a window of opportunity for domestic chip manufacturers to break into the automotive supply chain.