In a Las Vegas hotel, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang took the stage and pitched a futuristic idea to his audience — robots as "AI immigrants."

In an era when manufacturing is stuck in a labor-shortage quagmire, Huang's words sound both like a remedy and a reassurance.

While many around the world worry that automation will trigger mass job losses, this tech opinion leader offered a very different lens: "With robots, new jobs will be created."

It was, without question, a forceful intervention in the current debate over artificial intelligence and automation.

As demographics shift and economies transform, robotics is moving from a distant notion to a practical tool of production. Huang sketches a future where robots and humans work side by side — not a zero-sum replacement game.

Is that an optimistic vision, or a pragmatic reading of how industries evolve?

The global labor crunch and the inevitable rise of robotics

Manufacturing is facing a worldwide labor crisis.

Korn Ferry's Future of Work — Global Talent Shortage report argues that it's not robots displacing humans so much as a lack of talent to fill the jobs.

Korn Ferry finds that by 2030, the global talent shortfall will exceed 85 million — roughly Germany's population; left unaddressed, the shortfall could lead to about USD 8.5 trillion in unrealized annual output by 2030, equivalent to the combined annual output of Germany and Japan.

Financial and business services organizations face the largest gaps, reaching 10.7 million by 2030, with unrealized annual output as high as USD 1.3 trillion.

The report shows Asia-Pacific among the most affected regions, with China and Japan hit hardest. By 2030, China's unrealized annual output due to talent shortfalls will be USD 1.434 trillion, mainly in finance and business services; Japan's will be USD 1.387 trillion, primarily in manufacturing.

Several major APAC financial centers are also trending toward severe gaps. By 2030, Hong Kong and Singapore face talent shortfalls of 80% and 61%; the associated unrealized annual output equals 39% and 21% of their economic base. Australia and Japan stand at 25% and 24%; Indonesia at 19%.

World Population Prospects 2024 shows global population will likely keep growing for another five to six decades, peaking in the mid-2080s — rising from 8.2 billion in 2024 to about 10.3 billion, then easing to 10.2 billion by 2100.

The probability of a peak this century is high — around 80%, up sharply from 30% in 2013. The 2100 total may be about 700 million fewer than earlier projections, as several major countries' fertility rates undershoot expectations, especially China's.

On January 17, 2025, China's National Bureau of Statistics reported preliminary figures: in 2024, the population aged 60 and above reached 310.31 million, or 22.0% of the total; those 65 and above numbered 220.23 million, accounting for 15.6%.

Aging is only part of the story. The younger generation's waning interest in manufacturing work is just as telling.

In the United States, even though manufacturing wages typically top those in services, young people still gravitate toward office jobs over factory posts.

Germany, despite its long vocational training tradition, has seen a rapid decline in manufacturing apprentices over the past decade. This shift in occupational preferences is reshaping labor markets across the globe.

Meanwhile, robotics is progressing at a breathtaking pace.

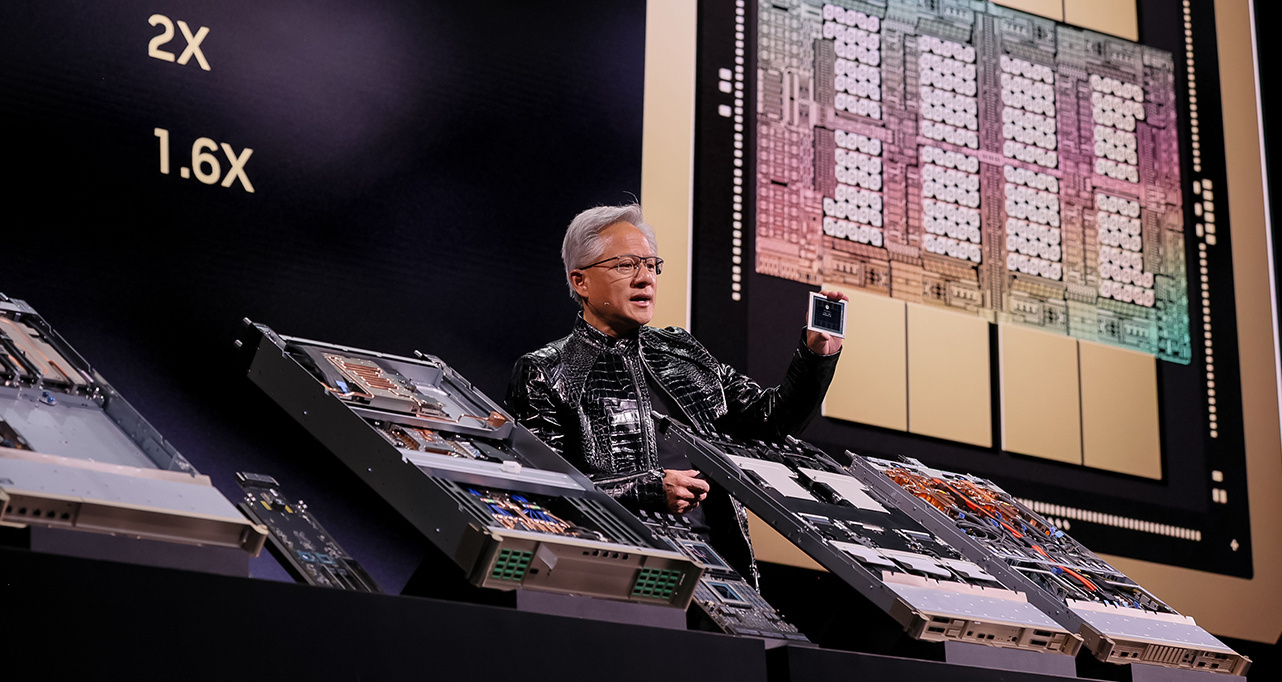

Image source: NVIDIA's Weibo

The International Federation of Robotics' World Robotics Report 2023 shows global industrial robot sales hit 553,000 units in 2022, up 5% to a record. The installed base reached about 3.9 million units, up 12%. From 2017 to 2022, annual sales grew at a roughly 7% compound rate.

Sales rose across Asia-Pacific, Europe and the Americas, with APAC remaining the largest market and still gaining share. Some 73% of 2022 sales were concentrated in APAC.

In August 2025, People's Daily reported — citing the 2025 World Robot Conference press briefing — that China's industrial robot market sold 302,000 units in 2024, marking 12 straight years as the world's largest industrial robot market. On the production front, China is the world's biggest robot producer: industrial robot output rose from 33,000 units in 2015 to 556,000 in 2024; service robot output reached 10.519 million units, up 34.3% year on year.

It's worth noting how far capabilities have advanced. A decade ago, industrial robots mainly handled repetitive tasks like welding and painting; today's collaborative robots can work shoulder to shoulder with humans on precision assembly. Robots are no longer just arms — they're gaining perception, learning and decision-making.

The collision of that technological curve with labor shortages has opened a historic window for large-scale adoption.

Huang's framing of robots as "AI immigrants" is no accident — just as migrants have historically filled labor gaps, robots are starting to do the same.

Unlike traditional immigration, these "AI immigrants" arrive without social-integration friction — and may well catalyze economic transformation.

How "AI immigrants" create jobs: moving beyond the replacement logic

When Huang says robots will create new work, he's drawing on historical precedent.

Every major technology revolution has stirred fears of mass unemployment; time and again, it has produced unprecedented roles instead.

The 19th-century Industrial Revolution brought factory managers and machinists; the 20th-century IT revolution birthed programmers and data analysts. The spread of robotics will likely follow that arc.

In practical terms, "AI immigrants" will generate jobs in three main ways:

First, the robotics industry itself becomes a new engine of employment.

According to the World Economic Forum, by 2025 half of all work will be done by machines; many human roles will disappear, but many new ones will emerge.

Specifically, by 2025 robots and AI will create 97 million new roles — from robot design engineers and machine-learning specialists to automation system maintenance staff. The Forum's research covers the world's 300 largest companies, employing around 8 million people globally.

NVIDIA, for its part, has been investing in robotics and adding related roles — not just technical posts but emerging jobs such as robot ethics specialists and human–machine interaction designers.

Image source: NVIDIA

Second, robots lift productivity, expand economic scale and indirectly create jobs.

Studies find that companies adopting robots often cut production costs and improve quality, widening their market share. That kind of expansion tends to increase hiring, not reduce it.

Consider a global automaker that introduced robots on its lines: headcount has risen over the past five years, because automation enabled more customized models and opened new markets.

In June 2025, China National Radio reported that PwC's 2025 Global AI Employment Barometer shows AI-driven productivity gains have quadrupled, with a 56% wage premium; even in the most automatable roles, employment is growing.

Wages keep climbing: in 2024, workers with AI skills earned an average 56% premium — twice the 25% a year earlier.

Surprisingly, even among roles most affected by AI, the number of positions rose 38%, albeit slower than in less-affected roles.

On per-capita income growth, AI-exposed industries (27%) outpaced less-exposed ones (9%) by a factor of three. In AI-affected roles, the pace at which skill requirements shift is 66% faster than before.

Third, robots free humans to take on higher-value work.

In manufacturing, once robots assume repetitive and dangerous tasks, workers can pivot to supervising, programming, maintaining and optimizing robot systems — roles that demand more advanced skills and pay better.

The shift doesn't happen overnight; it's coupled with upskilling.

As Huang puts it, "When the economy grows, we hire more people." Economics supports that view — automation raises productivity, lowers prices, boosts real incomes, stimulates demand and ultimately expands the economy and total employment.

Industrial transformation and HR restructuring in the robot age

The "robotics revolution" Huang envisions is not just technological; it's a deep reordering of the economy and human resources. The transition will reshape our work on three levels.

At the industry level, robotics is changing manufacturing's competitive landscape. Traditional labor-cost advantages are giving way to automation advantages.

Earlier data from Boston Consulting Group suggest that U.S. manufacturing can cut production costs by 18% by 2025 through AI and automation.

That shift will prompt a rethink of manufacturing footprints — no longer chasing low labor costs alone, but weighing automation maturity, supply-chain efficiency and proximity to markets. The resulting geographic reconfiguration will create new regional opportunities and reshape employment.

At the company level, robot integration is remaking workplace organization.

Early automation often took an "all or nothing" approach — a line was either fully automated or fully manual. Today's "AI immigrant" model is more flexible, with robots and humans forming complementary teams.

In global logistics warehouses, for instance, robots move shelving while human employees focus on the more complex picking and packing. This kind of collaboration not only raises efficiency, it also lightens the physical load on staff.

At the worker level, the robot era demands new skill mixes.

"Zhaopin's data show that 36% of companies have already provided substantive support for employees using AI, up 13 percentage points from 2024 — a sign that strategies are shifting from ‘using AI' to ‘empowering people through AI'," said Zhaopin CEO Kang Yan. In HR, Zhaopin has launched systematic hands-on training in AI applications and programs on AI innovation, helping employees swiftly adapt to ‘human–machine unit' collaboration and explore effective paths for organizational evolution.

As robotics spreads, demand will grow for STEM skills — alongside critical thinking, creativity and complex problem-solving. The goal isn't to turn everyone into a robotics expert; it's to build the capacity to work with AI: understanding robots' strengths and limits, managing systems well, and playing to human advantages where machines fall short.

Even so, the transition won't just happen — nor will it be painless.

Automation's impact is uneven: lower-skilled workers face greater risk of displacement, while higher-skilled talent is more likely to benefit. That requires governments, companies and educators to collaborate on robust reskilling systems and social safety nets.

As Huang says, robots are "immigrants," not "replacements." But making that vision real will take forward-looking policy and a collective push.

Image source: NVIDIA's Weibo

Huang's "AI immigrant" frame offers a positive way to read robotics' impact, without denying the challenges of transition. The real test is how we manage the shift — maximizing the upside while minimizing social costs.

As robots "immigrate" into our economic systems, they bring not only productivity gains but a fundamental change in the nature of work.

That may be the core of Huang's view: in a time of rapid technological evolution, we should move beyond fear, embrace change, and make sure its benefits reach everyone.

Robots aren't here to steal our jobs; they're arriving with new ones.

But that future won't build itself. It will take smart policy, sustained investment in education, and a fresh look at the nature of "work."

In the age of "AI immigrants," humans aren't being pushed to the margins; we're being redefined — shifting from executors to designers, supervisors and innovators.

That is likely Huang's deeper message: in a future of human–machine symbiosis, human creativity will be more valuable than ever.

Epilogue

History rhymes — it never repeats.

Each wave of technology lands with fears of replacement, yet humanity keeps carving out new frontiers beyond those fears. By calling robots "AI immigrants," Huang turns the narrative from man-versus-machine to man-and-machine coevolution.

Labor shortages aren't a temporary shock; they reflect a long-term interplay of demographics, economic transformation and technological advance. Robots, the "new immigrants" of our time, are quietly filling gaps on production lines worldwide.

Their meaning runs deeper than substitution — it's a liberation of productivity and a revaluation of work. As robots handle repetitive, precise and dangerous tasks, humans can move toward domains that demand creativity, empathy and strategic thinking.

This isn't blind optimism. It's a rational reading of history and data. From steam engines to computers, technology hasn't erased work; it has erased certain kinds of work while creating richer, more varied roles. The real challenge isn't the tech itself, but whether we can learn fast enough, adapt, and build systems that cushion the pain of transition.

Huang's claim, then, is less a prediction than an invitation: to welcome the coming collaboration revolution as builders, not as defenders. The future doesn't belong to machines, nor to a retreating humanity — it belongs to those who harness technology to extend human capabilities.

In the age of "AI immigrants," our most vital role is to give machines direction, design rules for collaboration and infuse the future with human warmth. Robots won't take our jobs; they will force us to rethink what only humans can do — and will always be worth doing. The answer lies in our evolving capacity to create.