Global sourcing in the auto industry

McKinsey & Company --- Although the world's big carmakers have had global reach for decades, they have been slow to take advantage of low wages in China and India to supply inexpensive parts to their assembly plants in Europe, Japan, and North America. The OEMs neither trusted the quality of Chinese and Indian components nor regarded the companies that manufacture them as any more efficient than the reliable existing suppliers in geographically closer countries such as Mexico and the Czech Republic. As recently as 2003, China exported just $4 billion worth of auto parts—mostly low-quality aftermarket items rather than original-equipment components used in the assembly of cars.1

Yet auto manufacturers are now rapidly shedding their skepticism. As domestic car markets in China and India took off in recent years, suppliers there made such big strides in quality and efficiency that the best of them are close to meeting world-class standards. Moreover, for certain components, locations such as Eastern Europe and Mexico are no longer as competitive as they once were. Meanwhile, cutthroat market conditions are forcing auto manufacturers into perpetual belt-tightening mode. They have no choice but to trim their costs constantly, since over the next ten years the price of a base-model car is likely to remain flat in real terms—even as carmakers add expensive new features to entice consumers or to comply with tougher government regulations.

Carmakers are now racing to buy as many bargain-basement parts as possible in low-cost countries and urging the same policy on top-tier global suppliers, such as Bosch, Denso, and TRW Automotive, which buy thousands of parts for the large preassembled modules they deliver to final-assembly plants. The cost savings may be enormous: carmakers could cut their parts bills by up to 25 percent. A company that manufactures about five million vehicles a year could theoretically lighten the tab by more than $10 billion annually.

Realizing these savings in practice won't be easy, however; buying auto parts is more complex than snapping up cheap shirts and plastic toys. Carmakers and their suppliers forge multiyear relationships that are difficult and expensive to unravel. Over time, a host of shifting factors, from exchange rates to rising wages, can turn what might initially have looked like a great deal into a costly mistake. It is therefore vital to understand how costs will evolve, so that today's sourcing decisions look smart ten years down the road.

The sourcing challenge

Compared with companies in industries such as electronics and textiles, carmakers and their parts suppliers face difficult challenges in global sourcing. Auto parts factories often require large up-front investments, which are usually paid off over the five- or seven-year life of a typical car model. Suppliers frequently spend the year or two before a car's launch refining the design and production process of its parts. Once assembly begins, the carmaker expects suppliers to find cost reductions through engineering changes or manufacturing improvements. Even after retiring a model, the carmaker often continues to buy replacement parts for old cars still on the road. And many parts require expensive production tools that can't be replicated easily or shifted quickly to rival suppliers.

Moreover, the carmakers' long-lasting relationships with their suppliers mean that traditional ways of estimating components costs—for example, comparing current wages, energy prices, logistics times, and shipping fees—can be inadequate or misleading. Carmakers should judge how these factors are likely to evolve and interact over, say, five to ten years; otherwise, a 10 percent savings may later balloon into a 10 percent increase.

One example of the way shifting conditions can quickly alter the math of global sourcing comes from China's aluminum industry. In just a few years, surging demand has transformed the country from a net exporter into a substantial importer. This development drove up the average price of aluminum on the Shanghai spot market to $1,428 a ton in 2003—23 percent more than the average price on the London Metal Exchange. It might have a similar effect on the cost of many aluminum car parts, from engine blocks to suspension components. In addition, exchange-rate uncertainty is higher than usual as US pressure on China to uncouple the renminbi from the dollar mounts. If, as many analysts believe, a freely floating renminbi were to appreciate against it, most of the anticipated savings from sourcing in China would vanish.

Judgments on which parts to manufacture in low-cost countries must therefore be made carefully and without preconceptions. Conventional wisdom, for instance, holds that labor-intensive parts are the best candidates for sourcing in such locations, but this isn't always true. Consider the massive metal-stamping dies that carmakers use to bend sheet metal into fenders and other body parts. These dies are manufactured using expensive metal-cutting machinery. Typically, such capital-intensive work stays close to home. But the production of dies is shifting rapidly from North America to China because government-sponsored access to cheap capital allows suppliers there to buy the machinery at low cost, and it is then operated almost around-the-clock by the country's huge workforce. In this case, China has transformed its labor cost advantage into a capital utilization advantage as well.

Sourcing in low-cost countries can undoubtedly be tricky, but carmakers have little choice, for chronic overcapacity and merciless competition have kept a lid on auto prices in the world's main markets for more than a decade. The inflation-adjusted price of the basic version of one of Europe's most popular models, for instance, held almost constant from 1999 to 2002. Yet during that period, its maker dramatically upgraded the car's standard equipment by adding airbags, antilock brakes, a more powerful engine, and sophisticated electronics to help drivers maintain control when they skid. To remain competitive, carmakers will need to reduce their components costs by as much as 30 percent over the next decade.

.jpg) @@page@@

@@page@@

Making the sourcing decision

As carmakers plan for the future, how can they negotiate their way through this minefield of ever-changing cost variables and choose the cheapest source for a bewildering array of parts? Which locations make the most sense over the long haul: the carmakers' home markets, nearby low-cost countries, or new frontiers such as China and India2 A sensible first step is to sort an automobile's hundreds of mechanical parts into clusters based on characteristics such as the balance between the cost of labor and capital, the importance of raw-materials costs, and the technical know-how suppliers must have to produce the parts.

Some parts are so bulky (fuel tanks) or so easily damaged (windshields) that they can't be shipped long distances economically; carmakers must source such items close to home. For the rest, we have identified five main clusters: technically sophisticated parts whose manufacture requires little labor, average parts, technically sophisticated parts with high labor requirements, simple parts that have a significant labor component, and parts whose cost is driven chiefly by raw materials. Once a carmaker organizes its shopping list in this way, each location can be evaluated according to the key cost factors, including local wage rates, the suppliers' engineering capabilities, and annual rates of productivity improvement. The crucial final step involves predicting how various factors, such as the ability of the suppliers to improve their productivity and the quality of their parts, will change over a car model's five- to seven-year life cycle—in each of the possible locations.

The results of such an analysis can be surprising . Consider the example of a US carmaker looking to buy plastic radiator fans, which cost only a few dollars. This is the kind of simple component you would expect to be sourced from China or India almost automatically. The truth is that added shipping charges and the higher cost of doing business in these countries wipe out any savings from outsourcing to them. For North American carmakers, Mexico is now the cheapest place to buy this part, and it is likely to be the cheapest place in ten years.

.jpg)

Nevertheless, savvy carmakers should plan for the day, a few years off, when low-cost countries become competitive for certain components. A German carmaker considering whether to buy cast-aluminum engine blocks in India, for instance, would decide not to do so—at least for a car model to be introduced in 2004. Engine blocks manufactured in Eastern Europe are clearly cheaper at the moment, and that isn't likely to change soon, because aluminum prices in India are relatively high and unlikely to fall until new production capacity comes on line toward the end of the decade. In addition, the suppliers' capital costs and profit margins are higher there.

The picture is likely to look quite different for a new model brought to market in 2010. By then, the price of aluminum in India should be in line with levels elsewhere, and the cost of capital should fall somewhat as liberalization and other factors push down interest rates. The productivity of Indian suppliers is likely to improve at a much faster pace than that of their counterparts in Eastern Europe—or indeed in Germany itself—and this ought to help them cut their unit labor costs and improve their capital efficiency. Meanwhile wages, which will probably rise only modestly in India, are projected to rise by up to 10 percent a year in Eastern European countries as they race to catch up with their western neighbors in the European Union. A similar increase occurred in Spain after it gained membership, in 1986.

Under these assumptions, by 2010 India will have a cost advantage for this kind of part over both Germany and the countries near it. Despite India's current cost disadvantage, a company might want to take the long view, in hopes of reaping the rewards later on, by locking in some high-quality Indian production capacity right now, at least for a small part of the volume.

For some parts, by contrast, carmakers would be wise to move production to China and India immediately and on a large scale. An air-conditioning compressor valve made of machined steel is a good example. Western European carmakers now pay about $7 for the part, with labor accounting for about 70 percent of the cost. Thanks to low wages in China and India, it obviously makes sense to have companies there supply the valve; the savings are immediate even given the likelihood that using suppliers in a distant location may involve some higher costs, such as a 60-day cushion of inventory instead of the 14 days needed with a manufacturer close to home. Moreover, the savings are likely to grow over the coming decade as labor costs in China and India rise more slowly than those in Europe, Japan, and North America.@@page@@

The way forward

Over the longer haul, carmakers can increase their economies from global sourcing by adjusting their own processes and product requirements to match the capabilities and characteristics of manufacturers in China and India. When a company designs new models, for example, it can adjust its engineering specifications in order to increase the number of parts that can be sourced from low-cost countries—for instance, by working around the suppliers' technical limitations or replacing automated assembly processes with manual labor. Complex components, such as brake calipers and their housings, which are currently bought from suppliers as preassembled units, could be broken down into single parts, some of which can be produced almost anywhere. This approach must be executed in partnership with the top-tier supplier, which would likely keep the responsibility for final assembly and testing.

Companies can also reengineer parts to reduce their technical complexity. One European carmaker found that Chinese and Indian suppliers lacked the know-how to make a coil suspension spring. Since bringing them up to speed would have been too costly and time-consuming, the company's engineers redesigned the steel spring so that it was easier to manufacture but still matched the original's performance. They also opted for a high-heat process (rather than the advanced cold process originally planned) because it was within the suppliers' capabilities. These decisions yielded 20 percent cost savings, even with customs duties and higher costs for investment, shipping, and inventory.

Sometimes an even simpler change in the production process will do the trick. Instead of using expensive automated assembly lines to machine large parts such as engine blocks or cylinder heads, for example, suppliers can rely on manual machining tools that require more labor to operate. Because of low wage rates, the lower capital investment more than compensates for the cost of the additional manpower.

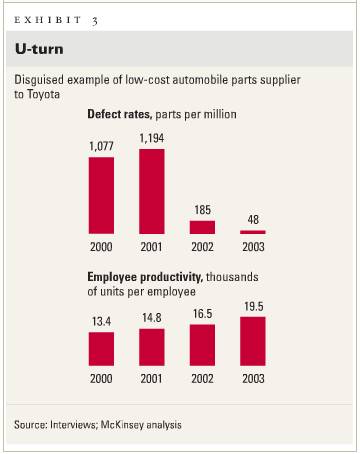

Some carmakers take a different tack. In 1999 Toyota Motor, for example, intervened directly to help several Indian suppliers of steering components implement the Toyota production system. It sent Japanese experts to teach Indian workers the techniques of lean manufacturing, from smoothing out spikes in production volume to error-proofing individual production steps. The results were remarkable. Over the next four years, one ball-joint supplier cut the number of defects from 1,000 for every 1,000,000 parts to fewer than 50—roughly equal to the defect rates of established Toyota suppliers elsewhere. Over the same period, the supplier's labor productivity increased by almost 50 percent .

The downside is that this approach incurs additional costs that eat into the overall savings, since carmakers must establish permanent local offices staffed with engineers and production specialists to coach suppliers as they climb the learning curve. This expense is difficult for many carmakers to justify; because of disjointed accounting practices, it usually lands on the books of the engineering department while the savings accrue to the purchasing department.

All in all, automakers must change their operations fundamentally if the rush to global sourcing is to generate lasting value. Top management should prioritize the product clusters it wishes to evaluate, set aggressive cost-savings targets, and stick to them over time. Purchasing departments will have a growing need not only to keep experienced people on the ground in low-cost countries but also to focus on developing the suppliers' capabilities rather than simply haggling over prices. Furthermore, automakers will have to attract and nurture talented local managers—a steep challenge given the number of companies, in a variety of industries, fighting over a limited pool of people with the necessary experience and language and technical skills.

The shift to parts suppliers in low-cost countries will happen only gradually as old car models are retired and replaced by new ones

Even the most committed carmakers will need years to wring the maximum savings from global-sourcing initiatives. The shift to suppliers in low-cost countries will happen only gradually as old car models are retired and replaced by new ones. The pace will vary from one company to another. Some of those with close-knit networks of suppliers may be slow to shift contracts away from them. (Many Japanese carmakers will fall into this category.) Moreover, the high cost of closing factories and laying off workers in Japan and many parts of Europe will make it hard to justify such moves. By contrast, the nature of the ties between US carmakers and their suppliers may facilitate the shift to low-cost locations as quickly as model cycles allow; already, Ford Motor and General Motors seem to be pushing more aggressively to buy more parts in China and India than are their rivals in Asia or Europe. European carmakers appear to fall somewhere between their counterparts in the United States and Japan.

In all three regions, political sensitivities about moving jobs offshore may slow the trend, particularly for parts still manufactured in the carmakers' home countries. But in the longer term, the intensity of competition will prevent such considerations from stopping the race to buy cheaper parts. Car companies that plan carefully, move forward with deliberate speed, and adapt their processes to suit the needs of low-cost suppliers will likely generate savings that persist over time rather than slip away as conditions evolve.

Notes

1 When we speak in this article of global sourcing in the automotive industry, we do not mean the sourcing of parts in a given country for use in car plants there. (China's domestic parts industry is indeed booming, along with domestic demand for cars and trucks.) This article addresses only the purchase of parts in one country for use in the factories of another.

2 We don't exclude the possibility that other countries, such as Brazil or Vietnam, might emerge as low-cost options, but China and India are likely to be the dominant players and thus receive the bulk of our attention here.

Gasgoo not only offers timely news and profound insight about China auto industry, but also help with business connection and expansion for suppliers and purchasers via multiple channels and methods. Buyer service:buyer-support@gasgoo.comSeller Service:seller-support@gasgoo.com