Picture a procurement chief at a legacy automaker negotiating across the table from the CEO of an AI‑chip startup. The papers between them may no longer be a simple supply contract and a price list, but a data‑sharing pact, a software revenue‑split plan, and a joint development timeline. Scenes like this are increasingly common across the global auto industry — the century‑old, linear supply chain is giving way to a more complex, more dynamic, and far more elastic web.

Image source: Shetu

The old playbook no longer works: OEM–supplier ties are being rewritten

"In the past, we knew exactly where we stood," said a senior executive who has spent two decades at a multinational parts supplier. "As a Tier 1, we took clear requirements from the OEM, broke them down, and delivered on time. Now an OEM might suddenly ask us to open up low‑level data — or bring in a software firm to co‑develop."

That unease says a lot: the unit of competition in autos is shifting from a single company to an ecosystem. The old supply chain was a pyramid — OEMs at the top, with Tier 1s and Tier 2s stacked below, information and instructions cascading down like a precision conveyor. The logic prized control and efficiency, squeezing costs through scale, long‑term contracts and stable tech roadmaps.

Now, three forces have snapped that line:

First, software–hardware decoupling has turned the car into an upgradable smart terminal. Software updates moved from "annual" to "monthly," even "weekly." The supply base has to respond fast — yet traditional parts development cycles take 18 to 24 months and simply can't keep up.

Second, the pace of intelligent tech iteration — especially in autonomous driving and smart cockpits — is blistering. OEMs found that relying on themselves and a few legacy suppliers won't match the speed of innovation. They have to reach into a more open tech ecosystem.

Third, user data and experience are more valuable than ever. Value is shifting from manufacturing and sales to lifetime services. Whoever understands and serves users better holds the profit engine — which demands supply networks that can feed back data in real time and generate insight.

These shifts force the supply base to become more elastic, more open, more collaborative. The rigid chain gives way to a flexible, multi‑connected web. In that web, OEMs, traditional Tier 1s and Tier 2s, tech firms, software vendors, data service providers — even energy companies — link up and work in parallel.

Old meets new: from control to co‑creation

To grasp what's changing, look at the logic beneath the structures. The chain was born of the industrial age — built for maximum efficiency under certainty. The web is the digital‑age response — built to adapt and to generate new things amid uncertainty.

The sharpest clash shows up in black‑box versus white‑box delivery. Traditionally, Tier 1s deeply bundled hardware and software and handed over a black box. OEMs cared about inputs and outputs, not how it worked inside. That protected supplier IP and made integration easier.

With software now defining the car, OEMs want to hold the vehicle's "soul" — namely the software architecture and user experience. They're pressing suppliers for white‑box or gray‑box options that open up low‑level interfaces, data and even portions of source code. Volkswagen's latest SSP platform, for example, explicitly requires suppliers to align with its unified software architecture.

That strikes at the business core of traditional suppliers. Many have said publicly that decades of proprietary know‑how are being pushed toward "open." Their edge must move up into software, algorithms and chip design, or down into materials science. Otherwise they risk becoming commoditized pipes, with margins squeezed ever thinner.

New entrants, reshuffled power

The expanding web decentralizes power. New centers keep emerging, leveraging dominance in a core tech field to force their way into autos — and reset the rules.

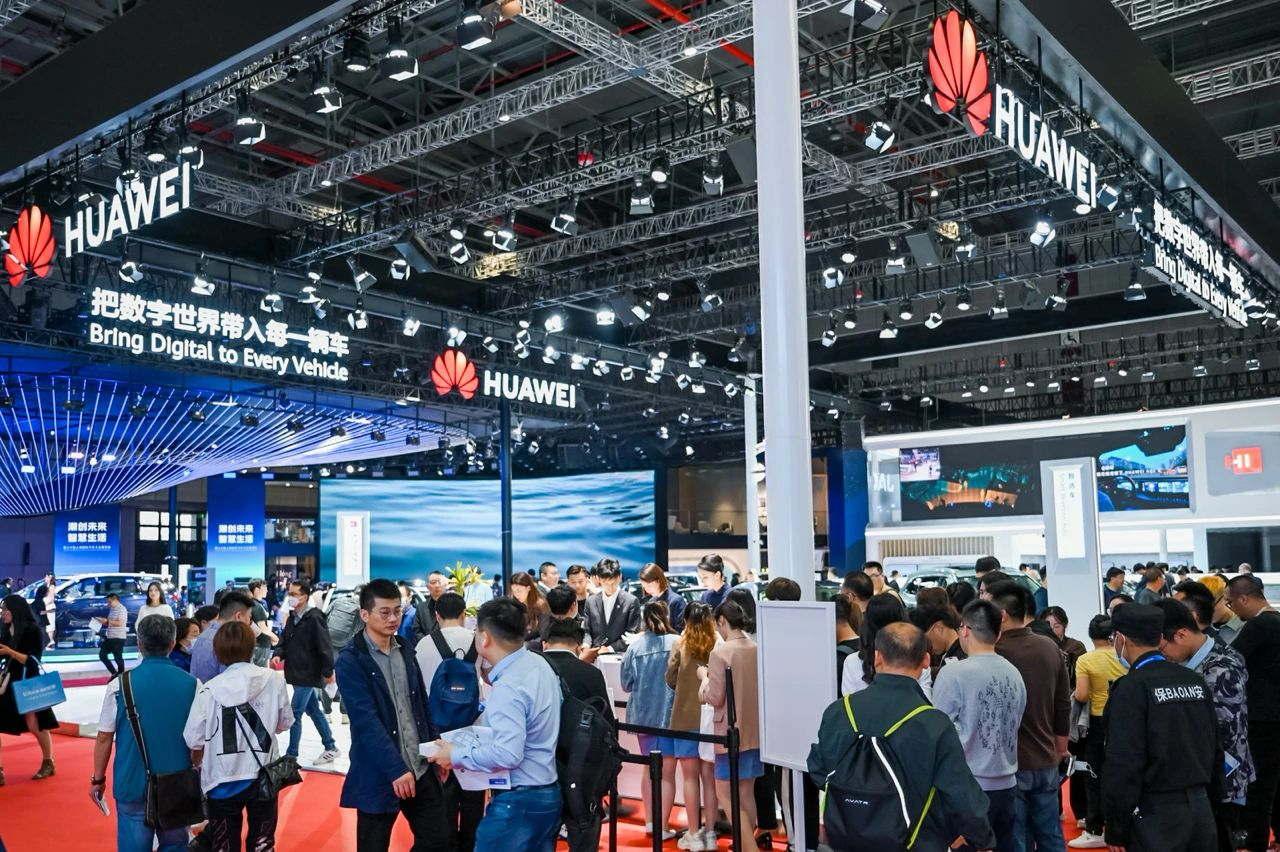

Tech firms bring the clearest "catfish effect." Take Huawei: it isn't a classic Tier 1 or Tier 2, but an "incremental" smart‑vehicle component supplier offering a full stack from HarmonyOS cockpit and autonomous‑driving systems to e‑drive and vehicle‑cloud services. OEMs both welcome and worry — they can plug intelligence gaps fast, but a strong Huawei stack could hollow out the OEM's brand. The AITO model built with SERES has done well commercially; the ensuing debate over "who holds the soul" reflects the push‑pull of coopetition.

Image source: Huawei Intelligent Automotive Solutions

Software and algorithm suppliers are also on the rise. In autonomy, companies like Momenta and QCraft focus on algorithm iteration; in cockpits, ThunderSoft provides OS middleware. They don't make hardware, yet their code puts them at strategic nodes in the network. Their bargaining power flows from replicability and speed — a mature algorithm can serve multiple brands across models, then get stronger through data loops, creating network effects.

Legacy OEMs are responding in different ways. Broadly, four routes:

Full‑stack in‑house: Tesla keeps almost all core software and hardware in house, building a deep, wide moat and maximizing integration speed.

Vertical integration: BYD goes deep in batteries, motors, power electronics and even semiconductors, keeping an exceptionally tight grip on its supply chain.

Ecosystem leadership: Volkswagen Group set up CARIAD to define a unified software platform from the top down, then build a supplier ecosystem around it.

Open collaboration: Many new‑energy upstarts and some legacy players "borrow the best," partnering with specialists across fields while focusing in house on product definition, brand and user operations.

For Tier 1 giants, the pivot is existential. Bosch, Continental and ZF all say they’re moving from "parts makers" to "technology companies," with strategies centered on hardware‑software fusion and services. Bosch not only supplies ESP hardware but also vehicle‑dynamics control software; Continental has bundled autonomy into "Assisted & Automated Driving Solutions." The aim is to transcend contract manufacturing and become next‑generation suppliers of integrated hardware, software and services.

Image source: ZF

Toward symbiosis: new paths, new challenges

The bargaining may be fierce, yet the direction is collaboration and symbiosis. A healthy web needs fresh, sustainable rules and business models. The industry is testing several ideas:

Joint ventures and co‑creation: By mid‑2025, Volkswagen, Mercedes‑Benz and BMW — together with Bosch, Continental and other top suppliers — 11 companies in total — announced a software alliance to co‑develop and share a core platform called "S‑CORE" based on open‑source principles. More than a simple JV, the alliance takes a code‑first approach to cut base software costs, and pilots a community for risk‑sharing and benefit‑sharing.

Capital tie‑ups: Strategic investment to lock in core resources. NIO and XPENG have spent heavily across chips and battery materials; legacy players like Geely deploy their funds widely across smart‑connected supply chains. Capital tightens ecosystem bonds.

Open platforms: Leaders open their tech platforms to attract partners and scale fast. BYD’s e‑Platform 3.0 and Geely’s SEA architecture are already open. It’s akin to Android: platform owners set standards and offer foundational capabilities to gain influence — and data value.

Still, building a sustainable symbiosis hinges on solving a few core issues:

How will data flow, and who owns it?

Data is the lifeblood of a networked collaboration — and the hardest to handle. Vehicle operating data belongs to the owner; development value belongs to OEMs and suppliers. Privacy, security and commercial boundaries are blurry, and the industry lacks common exchange protocols and valuation frameworks.

How do interfaces and standards build trust?

Standards are the skeleton of the ecosystem. If OEMs set closed, bespoke standards, supplier adaptation costs surge; fully unified standards, on the other hand, can stifle innovation. Some open‑source alliances — including those advancing SOA architectures — are charting a middle path by defining basic, general‑purpose interface specs.

How are software‑driven profits shared?

As OTA lets software create value continuously — think autonomous‑driving subscriptions — how should revenue be split among OEMs, software vendors, hardware suppliers and data providers? New sharing models are needed. In some cases, OEMs and suppliers agree to split subscription income tied to specific hardware at a fixed ratio, shifting supplier earnings from one‑off sales to recurring service fees.

Hidden reefs and risks: the fragile side of the web

Networks raise efficiency — and complicate risk. While they boost innovation, they also reveal points of fragility.

First, supply‑chain resilience faces a paradox. Global networks are most efficient in ideal conditions, yet geopolitical conflicts and trade barriers — the "gray rhinos" — can sever critical nodes. If a high‑end automotive chip or key software module is cut off for non‑technical reasons, the production network can stall. Companies must balance efficiency and security; regional footprints and backup supply lines matter more than ever.

Second, management complexity spikes. Running a chain with dozens of core suppliers is hard enough; governing a dynamic web of hundreds of diverse partners is a step‑change challenge for OEMs’ organization, IT systems and open culture. Many legacy teams in procurement, R&D and quality aren’t ready to work with small algorithm firms on equal, agile terms.

Third, liability becomes a legal and ethical thicket. If a car with autonomous functions crashes, is the OEM, the algorithm developer, the sensor supplier or the map provider at fault? Traditional product‑liability frameworks struggle with distributed, systemic responsibility. Industry and regulators need new attribution and insurance systems.

Lastly, small and mid‑sized suppliers risk marginalization. In winner‑takes‑most ecosystems, firms without hard technical moats or unique data value can be pushed out of the core. A vibrant industry needs large, medium and small players to thrive together. Preventing the web from turning into a private club for a few giants is an important governance question.

What wins next: who becomes the ecosystem’s organizing core?

By 2030, the supply landscape could look very different. A few things seem likely:

A handful of galaxy‑like super ecosystems will emerge — some built around top OEMs, others around tech giants. Each will run a tightly coordinated tech stack, data standards and business model, with limited interoperability across ecosystems. Choosing which one to join will be the defining strategic call for suppliers.

Core advantage will be redefined. For all participants, these capabilities may matter more than sheer manufacturing scale or cost control:

Architecture definition: the ability to define E/E hardware architectures or software service architectures.

Standard setting: the ability to shape standards for key interfaces and data formats.

Data operations: the ability to collect, process and analyze data to drive product iteration and service innovation.

Ecosystem governance: the ability to design rules, balance interests, and attract and motivate diverse partners to innovate together.

Ultimately, competition in autos is leveling up. It’s no longer product versus product or brand versus brand, but ecosystem against ecosystem — a contest of openness, innovation speed and collaborative efficiency. Whoever builds the fairest, most vibrant and sustainable ecosystem will attract the best talent, the newest technology and the most abundant capital — and win the next era.