“Future intelligent driving will largely revert to major Tier 1 suppliers, meaning automakers will essentially outsource their entire smart-driving systems.”

That assessment from Wang Xianbin, vice president of the Gasgoo Automotive Research Institute, made during a recent salon, is fast becoming reality. With the exception of a few holdouts like Tesla, XPENG, and Li Auto still gritting their teeth over in-house development, names like Huawei Qiankun, Momenta, DeepRoute, Horizon Robotics, and Nvidia are emerging as the new “souls” of intelligent vehicles.

Why? The answer is brutal: this is a game ordinary players simply can no longer afford.

In-House R&D? It’s Too Expensive!

What burns the most cash when building an intelligent car?

It isn’t the battery, nor the “big screens” or “luxury seats.” It’s intelligent driving. “The investment in R&D, the talent, and the requirements are incredibly high,” Wang puts it bluntly.

Just how high? Assembling a top-tier algorithm team easily costs over 100 million yuan annually in labor alone. Then there’s the bottomless pit of collecting and processing massive datasets, building computing centers, and conducting endless safety tests.

For automakers with razor-thin margins or sales volumes of just a few hundred thousand units, that burden is crushing. Even more painful is the reality that consumers might not even pay for it.

According to the latest research from the Gasgoo Automotive Research Institute, 65% of users want advanced intelligent driving, yet only 20% actually trust it. “Safety” is the top concern, cited by 60% of respondents.

Take the incident on January 6 in Nanning, Guangxi, where an Avatr 07 speeding down the road crashed into 15 vehicles, causing extensive damage and minor injuries. The online community immediately questioned whether the “Avatr driver assistance system had malfunctioned.” It wasn’t until ten days later—when police confirmed the driver was fully at fault and backend data showed the assistance system was inactive while airbags deployed normally—that the outcry subsided.

Rather than spending tens of billions on proprietary development, opting for a mature supplier solution allows for rapid feature deployment and partially transfers potential safety liability risks. The economics are clear to everyone.

As a result, the industry is seeing a clear split:

The “stubborn” in-house faction—Tesla, NIO, XPENG, and Li Auto—insists that smart driving is their brand DNA and must be controlled internally. Meanwhile, the vast majority of automakers are choosing to leave professional work to professionals.

Consider Huawei’s evolution: from simply selling components to the HI model offering full-stack solutions, and now to the “Harmony Intelligent Mobility Alliance”—deeply involved in product definition and sales for brands like AITO and Luxeed—alongside co-created new brands like “Qijing” and “Yijing” with GAC and Dongfeng.

In 2025 alone, its Intelligent Automotive Solutions BU shipped over 31.68 million components, with a total installation base of 976,000 vehicles. According to Jin Yuzhi, CEO of Huawei’s Intelligent Automotive Solutions BU, Qiankun smart driving will be equipped on 80 models this year, bringing the total installation base to 3 million units by year-end.

Momenta is taking the classic tier-one supplier route, a strategy defined by two words: broad alliances and multiple design wins. Deeply integrated with Toyota, GM, SAIC, and NIO, it has announced over 130 designated models as of mid-2025.

Image Source: Momenta

They aren't looking to dominate the ecosystem, but rather to carve out the largest slice from the biggest cake.

Then there’s Horizon Robotics, building a massive ecosystem alliance through an open “chip plus algorithm” model; and DeepRoute, which emphasizes deep integration over volume to create “blockbuster” products.

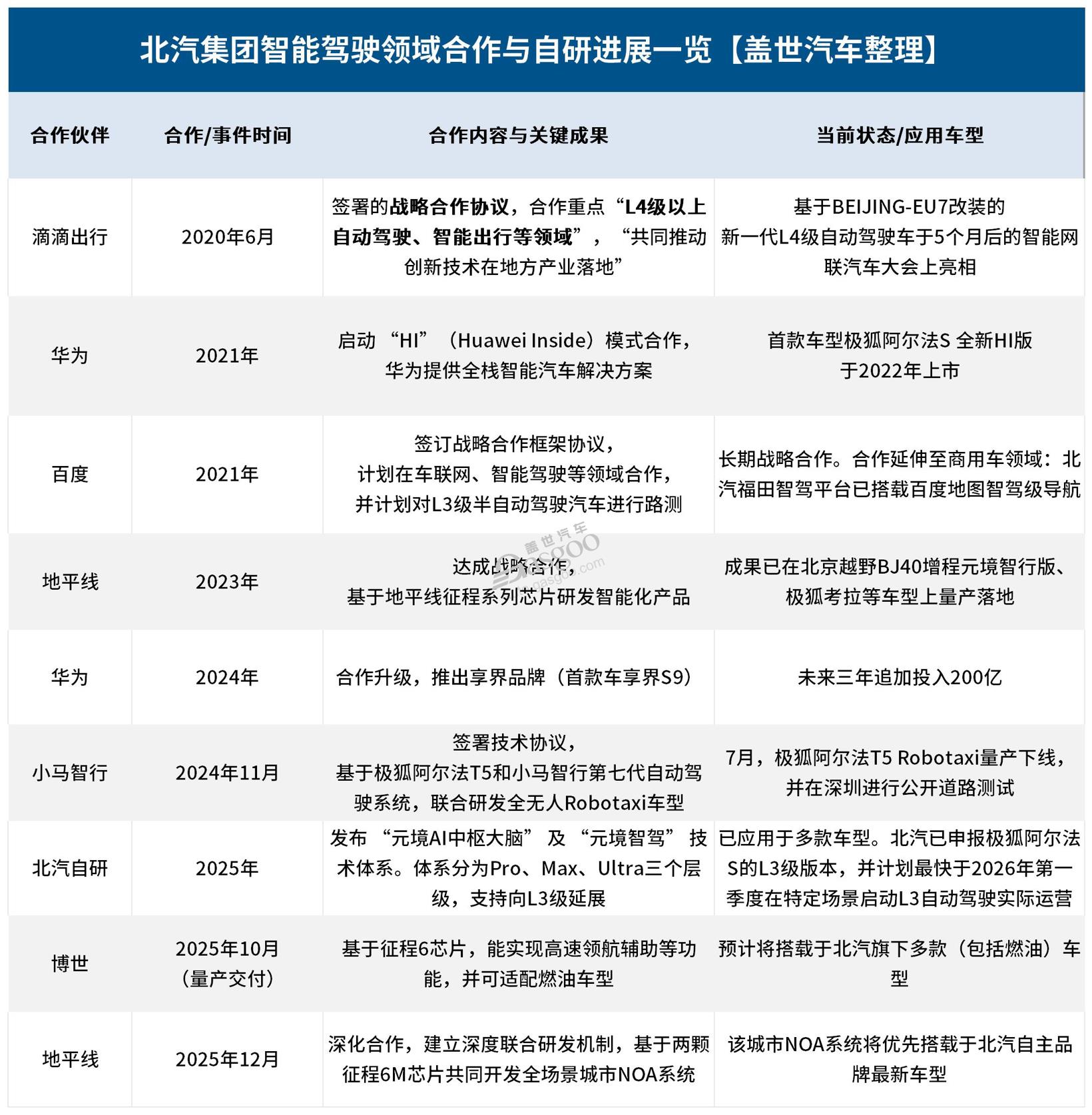

Even more telling is the strategy of companies like Chery and BAIC. They are no longer going all-in on one path but are simultaneously partnering with multiple suppliers, flexibly configuring different smart-driving solutions based on the positioning of specific models.

This trend of “leaving professional work to professionals” isn't unique to China. Wang Xianbin observes that “whether abroad or in China, most leading automakers are gradually shifting toward outsourcing.”

Globally, even multinational giants that once insisted on in-house development are re-evaluating their technological paths. It’s not just automakers: global parts behemoths like Bosch and Continental are also attempting joint ventures with WeRide and Horizon Robotics to accelerate their intelligent transformation.

Steep R&D costs, the risks of rapidly iterating technology, and insurmountable talent barriers are making outsourcing the more commercially rational choice.

A Tech Route Brawl: Whoever Has the Data Makes the Rules

Another deep reason automakers are outsourcing: the technological roadmap is too uncertain, making the risk of betting on the wrong horse incredibly high.

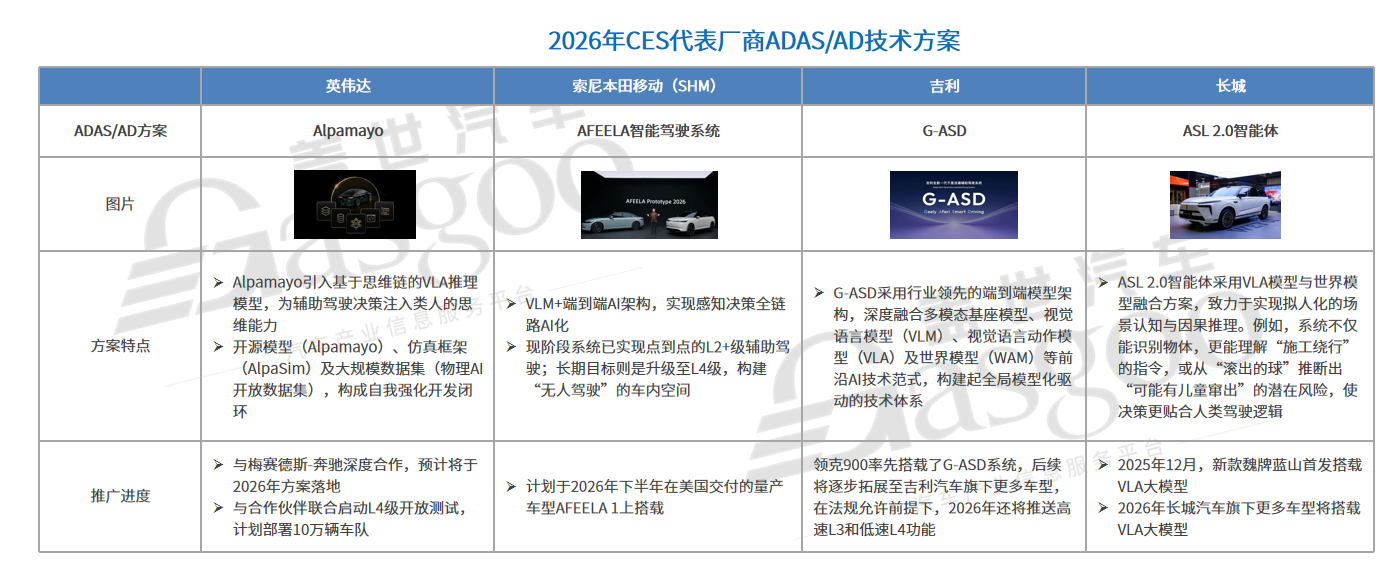

Wang Xianbin points out that the industry is currently exploring at least three mainstream paths: end-to-end, VLA, and world models. Which is better? No one can say for sure.

End-to-end models attempt to mimic human intuition, mapping sensor data directly into control commands for ultimate efficiency and performance ceilings. VLA (Vision-Language-Action) models aim to bridge the gap between visual perception and language understanding, allowing vehicles to not only “see” but also “comprehend” complex scenarios. World models are even more ambitious, seeking to build deep simulations of physical laws in a virtual world, teaching AI to reason and predict.

Each technological route represents a distinct philosophical approach to intelligent driving, with entirely different development paths, data requirements, and hardware architectures. “I believe this landscape will persist for a long time; it won't be limited to just VLA or world models.” Wang argues.

For automakers, this is tantamount to a massive gamble—betting on the wrong technological direction could mean wasting years of time and billions in capital.

The real deciding factor lies in “data dominance.”

Smart-driving systems aren't completed in one development cycle; they require massive amounts of real-world data to continuously evolve—the “data flywheel.” The more cars you have on the road, the more data you collect, and the smarter your system becomes.

By January 2026, thanks to millions of production vehicles globally, Tesla’s FSD cumulative mileage nearly doubled in ten months, jumping from 3.6 billion miles (about 5.79 billion kilometers). Yet, it still faces a gap of roughly 3 billion miles (about 4.83 billion kilometers) to reach its 10-billion-mile (about 16.09 billion kilometers) target.

Here, leading tech giants can leverage vast partner networks to acquire data scales far beyond any single automaker. Their powerful cloud computing infrastructures can support model training on clusters of thousands, even tens of thousands, of GPUs.

Take Huawei. According to its “Safe Travel Report” released on January 16, Qiankun smart driving has logged 7.28 billion kilometers, with 5.42 billion kilometers added in 2025 alone. Under its assistance, safety is reportedly 3.58 times that of a typical driver.

Image Source: Gasgoo Automotive Research Institute

This data isn't just cold figures; it’s the “fuel” for algorithm iteration. That is why it can rapidly roll out ADS 4.1 and preview the launch of ADS 5.0 later this year.

Consequently, in the premium market above 350,000 yuan, Huawei holds over half the smart-driving share, with an activation rate as high as 98%.

Meanwhile, the rise of simulation testing is further changing the rules of the game. “Through AI, such as Nvidia’s Cosmos world foundation model, we can safely and efficiently reproduce millions of kilometers of extreme scenarios in a virtual world,” Wang notes. “This accelerates system maturity and will significantly aid everyone's development rhythm.”

Whoever masters advanced simulation technology owns a faster learning curve.

With technological routes so diverse and rapidly evolving, and with data and computing power becoming the new moats, traditional automakers are finding themselves increasingly like “outsiders.” Outsourcing smart-driving systems is no longer just about cutting costs—it’s about securing the ability to continuously update technology.

In the realm of smart driving, stagnation means falling behind.

What Is the Automaker's “New Identity”?

When the “brain” is outsourced, where is the automaker's value? Will they be reduced to mere soulless “assembly plants”?

Not necessarily, but the role must transform.

Wang envisions the future car as an “intelligent life form that can perceive, think, and communicate.” To achieve that, smart driving alone isn't enough; it requires deep synergy across smart driving, cockpits, and chassis.

This is the new battleground where suppliers are competing. Huawei’s comprehensive upgrade of its “Five Major Solutions” for 2026 is a prime example: smart driving (ADS 5), digital chassis (XMC), smart lighting (AR-HUD), vehicle-cloud services, and the Harmony cockpit (Harmony Space 6). It is building a cross-domain, fused intelligent body.

This means partner automakers gain a highly coordinated “nervous system.” The benefit is an extreme user experience, but the challenge is that the space for automakers to define their own differentiation is compressed.

So, where should automakers pivot their core competitiveness?

They may no longer need to hire thousands of algorithm engineers, but they must become superior “product definers” and “experience integrators.”

Wang points the way: the smart cockpit. Because “compared to the high difficulty and safety demands of smart driving, the cockpit offers characteristics like easily differentiated and perceptible scenario experiences, making it a key focus for building vehicle differentiation right now.”

To translate: Smart driving is the “fundamental skill”—pursuing safety, reliability, and usability, where convergence is inevitable. The cockpit, however, is the “personality stage.” Whether through audio-visual entertainment, rest scenarios, multi-screen interaction, or voice assistants, the ability to craft unique experiences that move users is becoming the key to brand breakout.

Business models are shifting too. The value of a car is moving from a one-off hardware sale to full-lifecycle services covering “mobility, data, energy, finance, and software.” In this arena, tech companies that hold the user entry points and software capabilities clearly occupy a more advantageous position in value distribution.

An even more disruptive future is unfolding: when L4 autonomous driving matures, the car will transform into a “mobile intelligent space.”

Wang envisions this: “Could this vehicle serve as a physical carrier for display—say, for holding a small meeting or for leisure and entertainment?” By then, the autonomous driving system will be the basic utility—“water, electricity, and gas”—of that space, while the scenario-based applications, services, and content layered on top will become the new highlands of value.

In this transformation, no single player can dominate everything. Carmakers, tech companies, traditional Tier 1 suppliers, software developers, and content providers will reposition their roles within a more open, collaborative ecosystem to share the immense dividends of the smart vehicle era together.

So, who will call the shots on future smart driving? The answer is likely not one or the other.

Automakers cannot fully control core technologies, yet they firmly hold the ultimate power of brand, users, and vehicle integration. Tech companies hold the keys to algorithms and software but rely on automakers for mass-market deployment. Traditional Tier 1 suppliers, backed by deep engineering experience and a reputation for safety, remain irreplaceable in critical execution domains.

Wang predicts that “leading enterprises are expected to emerge in the vehicle and core supply chain ecosystem.” As it stands now, those leaders may not emerge from the automaker brands, but from the very top of the core intelligent supply chain.

The steering wheel of smart driving has never been so “decentralized.” Yet this revolution in division of labor isn't about right or wrong—it’s about efficiency. Only when the industry bids farewell to the romantic fervor for technology and returns to the essence of business and engineering will the curtain truly rise on a more mature, more dynamic era of intelligent mobility.